Portrait of the Artist as a Young Doctor, 1974. Black and white photograph.

Some of us who work with art, when confronted with a difficult situation, force ourselves to realize that, despite the magnitude of the problem, there are more crucial things in the larger scheme of life. Art is important, but it does not save lives.

Well, sometimes it does: Eric Avery's is one of those rare cases in which an art practice is intimately linked with a life-defining situation. While often artists have another profession, it is rather unusal to have a practicing doctor that works with equal passion on art-making. In Eric Avery’s work, two professions that appear to be radically different come together naturally within the same practice. Trained as a doctor in a rather difficult time in American history, Avery started early to use his artistic output as a way to raise awareness towards pressing health issues. Ignorance can equal death, as one of the eary mottos by Act Up warned. Or, as he put it in a print done about a refugee camp in Somalia, “Food is medicine.” Some of his prints have a distinct political purpose. As we all know, the official treatment of disease is informed by political agendas that vary in relation to the social group that is endangered. Since the late seventies, Avery has been an active printmaker. In the last few decades he has done performances in art settings in which he tests visitors for HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis C, and other diseases. His prints hark back to the history of printmaking as a way to spread a message and to reach a larger audience in public space. His long career can be looked up on his aptly titled blog, DocArt.com.

This interview was done via email.

J. Roca.

Jose Roca: You studied Medicine and are a practicing doctor. How did you become interested in art? When did you start making artworks and participating in exhibitions?

Eric Avery: I was cutting linoleum blocks in Pecos, Texas when I was 13, printing note cards that were sold in a yarn shop on Highway 80. I'm still cutting linoleum 47 years later. Printmaking has been a curse. I majored in art at the University of Arizona. I had a terrific printmaking teacher/mentor Andrew Rush. This was the Vietnam War time. My draft number was 7, so I would have gone to the war if I hadn't figured out how to continue my education. Andy said I always talked about being a doctor. He suggested I give it a try. I didn't think it was possible because I was an artist. Andy said I would always make prints and suggested I go have an interesting life and that my prints would fall like dandruff on my trail.

I took some science classes. I loved Biology and didn't have to take Calculus. I did good enough to get into medical school at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. This was during the early days in the development of Medical Humanities in the United States. I made prints all through my medical school years in Texas and then in New York City during my psychiatry residency training. In 1972, I silkscreened all 700 of my medical school's yearbook covers. My first exhibition was after medical school in 1974.

My first real woodcuts were made in Somalia, in a big refugee death camp in 1979 and 1980. If I didn't make prints in that place, I think I would have cracked. When I returned to Texas, I left the practice of medicine. I worked through all the death with my printmaking and had an important exhibit, "Images of Life and Death," in 1982. During this time, I added papermaking so I could print from three-dimensional wooden templates.

I've been making prints and paper and exhibiting regularly since 1982. In 1992, I returned to practicing medicine and became a psychiatrist specializing in caring for people with HIV/AIDS. I would have cracked during the really bad AIDS times if I didn't make prints. Cutting wood and linoleum, hand-rubbed printing, beating paper pulp from my work shirts, pressing paper with my hydraulic press- all of these physical acts move trauma from the brain out through the body. Printmaking is good medicine if you've got a lot of distress and emotional pain. The prints can be hard to look at and live with. They are almost impossible to sell. I've made a lot of prints related to HIV/AIDS. A bunch of my medical-related prints are in the ARS MEDICA Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. They are a part of the print history of the AIDS pandemic.

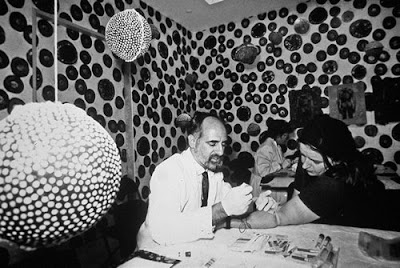

Healing Before Art: Public HIV Testing Action

Installation at Mary Ryan Gallery, New York City, 1994

A clinical art space to be used for the public HIV testing of art world representatives (artists, art dealers, collectors, curators).

Here, artist Sue Coe’s blood is drawn by Phil Muskin, M.D.

JR: Your work is often performance-based, doing medical tests in the context of an art gallery. Is the main intention of the work primarily to raise awareness of pressing health issues?

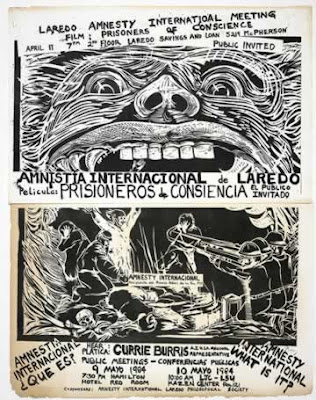

EA: I've used a lot of the print forms but I was always working to get the prints off the walls and connected to the life I was witnessing and living. After working in Somalia, I quit practicing medicine and didn't see patients for eleven years. I lived on the Texas-Mexico border and worked to help Central American and Haitian refugees fleeing for their lives. Their human rights were being abused by U.S. immigration policy. I made some really good prints about the war in Central America and about how I felt about my country.

Sixteen years ago, when my friends began to die in Houston from AIDS, my life turned back to the practice of medicine at my old medical school, The University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. I've worked as a psychiatrist in the HIV Clinic and on the medical wards since then and my prints, print actions and installations have been about health matters.

At UTMB, the Institute for Medical Humanities had developed into a multidisciplinary humanities program. I'm the visual artist on the faculty. One day of my week has been protected for me to work on the connection between visual art and medicine- to reflect upon what I do in my clinical practice.

JR: A practice that involves art and medicine would seem a sleight of hand, but it seems to have come naturally to you.

EA: It might be so now, but it wasn't thirty years ago. I've always thought that the relationship had something to do with space. I used photography to look at the literal spaces of healing. As my artistic and medical practices grew, I was able to ask art museums wanting to exhibit my work if I could create healing spaces in their museums. I flipped functions. Printmakers are always working with reversals. Several anthropologist friends helped me understand liminality and the neither/nor.

Allen Kaprow's blurring of the relationship between art and life was an inspiration. Warhol did it. It's an old story. I just blurred the line between visual art and medicine. I used my prints in clinical art spaces where medicine was practiced in the aesthetic dimension. Doctors practicing medicine in an art museum- it's a subversive practice in liminal space. Each art/medicine action has had an educational and instrumental purpose. A number have been done on World AIDS Day. They also raise conceptual questions about the relationship between visual art and medicine. I'm really proud of the questions my art/medicine actions have raised about the function of art museum and gallery spaces. Wouldn't it be fantastic if you went to an art museum for health care? I have only a small audience, but the print form, historically connected to social content and information dissemination, works for what I've tried to do with art/medicine.

JR: Speaking of dissemination, we are on the verge of the first pandemic in the new millenium. What are your ideas for Philagrafika 2010?

EA: Your blog posting of the Poli/gráfica de San Juan was an inspiration. Miler Lagos’ woodcuts on tree stumps led me to propose text woodcuts on The Print Center toilet seats (that would imprint bottoms) perhaps something related to HIV risk reduction. Jose Carlos Martinot’s printers in palm trees- why not health-related information on toilet paper, or printed wallpaper in front of the urinals?

I'm also excited about my proposal of prints depicting wounded Adam and Eve on the wall of The Print Center. These 3'x6' linocuts of Adam and Eve (via Durer, Cranach's first couple) will have them being attacked by vectors and modes of transmission of Emerging Infectious Diseases. The snake will be coughing Avian Flu. Title of my piece might be: "So Who Needs The Snake In Our Garden Of Eden." From these key index images I'll have other printed and photographic images that relate to the various infectious diseases.

And I am trying to conceptualize a small booklet or pamphlet that will work with the prints. When I last wrote to you I remember writing that we were just one mutation away from a pandemic. Recently the World Health Organization officially moved H1N1 to Level 6 pandemic status. By next winter's flu season, we are afraid that H1N1 will return in a more virulent form. The worst fear of Dr. Margaret Chan, Director-General of the World Health Organization, is that H1N1 will mix with H5N1 (avian flu, but anything can happen with the influenza virus).

I'm trying to connect my prints to Philadelphia and infectious disease. In 1792, the Yellow Fever was so bad in Philadelphia that the United States Capital moved to Washington D.C. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson fled the city. One of the first water treatment plants was built in Philadelphia in 1811 on the Schuykill River. I've got a great photo of this federal building with the Philadelphia Museum looming in the background. I don't know if the water treatment plant still exists. There is an inverse relation between amount of water flowing through a house and infectious diseases.

Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2000. 2-color lithograph with linoleum block print on mulberry paper collaged into molded paper (made from used surgical green towels) woodcut frame. 44" x 31" edition: 10.

Philagrafika 2010 will be happening during flu season. There should be a vaccine by then. But I want my piece for The Print Center to do something to educate about flu protection- something as simple as cover up each cough and sneeze or you will spread disease, or about the importance of hand washing. I was amazed in my HIV Clinic that my undereducated patients don't know what a virus (HIV) is, so I made a printed book to educate them. I might make a book about the influenza virus.

JR: It could be said that you are countering the dissemination of a contagious disease with the dissemination of information.

EA: You write so eloquently about printmaking as form. I think my work has something to do with what Philagrafika is about. As a psychodynamic psychiatrist, there is a natural connection between the unconscious and disease. Getting better involves connecting what's under to what's out. With prints, I'm thinking about Goya's Disasters as access to the worst in humans and his prints' dispersal and dissemination as connected to healing. A social worker gave me a line I use with my patients, "Getting real is the only way to heal." Emerging infections are a real problem. Avian flu is killing children in Egypt today. We are a mutation away from a global pandemic. As a printmaker I know a lot about the graphic and as a psychiatrist, I know a fair amount about the unconscious. Art as medicine: Why not?

Johnny Garrett is Dead. 1992. Woodcut on machine-made Okawara paper. 36" x 48" Edition: 10

Johnny Frank Garrett was just seventeen years old when he committed the brutal murder that sent him to death row. He was chronically psychotic then, a victim himself of unspeakable brutality throughout his childhood and formative years. Treated like an animal for most of his young life, he responded by behaving in the only way he had ever known- violently. Society should not be surprised; the priorities are all too clear. There is little money available to help abused children but plenty available to punish or kill them when they, in turn, offend by doing violence to others.

Now, the poor, damaged, confused life of Johnny Garrett was drawing to its end. What was he thinking, with just ten minutes’ existence left? What goes through a person’s mind at a time such as this?

We were some twenty Amnesty International members and other opponents of the death penalty gathered together. I like to think we were a dignified group with our simple handwritten signs, making our witness and our protest. Rain-filled clouds scudded by overhead and we huddled together for warmth, our candles flickering points of light in the gloomy night.

A few minutes before midnight, “they” arrived. A rowdy crowd of about 80 college students, mainly white youths in baseball caps. They had come to celebrate the death, to gloat over Johnny’s fate, and to taunt us. They taunted us because we cared, because we care about a man’s broken life and a bigger principle: that governments have no right to use the power we bestow on them to kill us.

“Kill the freak.” “Fry him.” “Remember the nun.” Their ignorance was extensive. Texas kills by lethal injection, not electrocution. They did not know Johnny’s history. And they did not know that the murdered nun’s convent community (together with the Pope and all Texas’ bishops) have appealed vociferously for clemency. They wanted their beloved Sister Tadea Benz to be remembered not with another murder, but with forgiveness and mercy. Their pleas for compassion went unheeded.

We stood in thoughtful silence under a stop sign. The mob roared its approval of Johnny’s murder under a dead tree. They counted down to midnight and the moment of execution. Voyeurs in the night, cheering as the hour struck.

Revenge is ugly. At least one death penalty supporter was so appalled at finding himself part of the grotesque display that he crossed the road and silently joined us. AI recruited new members that night.

Cameras flashed and snapped as the media came and went among us, seeking the usual superficial stories, bereft of depth or insight. I was asked what I thought of the circus under the dead tree. I said it epitomized so much that’s wrong with the death penalty. Executions encourage our most primitive instincts; they set a brutal and dangerous example to society. In short, they bring out the worst in people. The world is sick enough already, I told the reporter. Shouldn’t we be striving for a better way?

From "Witness to an Execution: Thoughts on the Killing of Johnny Garrett", by Mandy Bath ( A.I. International Secretariat, London, 1992.)

No comments:

Post a Comment